As I have been writing since 2011, China’s development lending was always likely to follow the pattern of other countries when they first “went out” (e.g. the US in the 1920s, USSR in the 1950s, Japan in the late 1970s). Because of little historical...

1/9

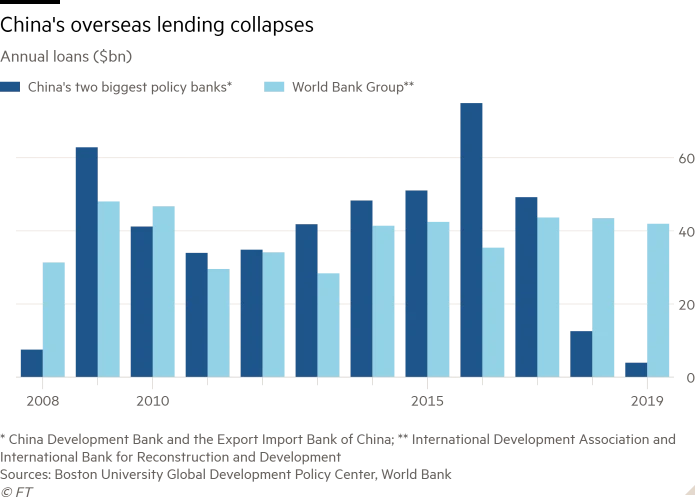

Good article. But while growing international criticism and rising trade tensions may have had some impact, as the article suggests, I don’t think they really explain the great reversal in BRI lending of the past few years.

As I have been writing since 2011, China’s development lending was always likely to follow the pattern of other countries when they first “went out” (e.g. the US in the 1920s, USSR in the 1950s, Japan in the late 1970s). Because of little historical...

knowledge and no previous experience, an early rapid rise in development lending would be driven mainly by underestimating risk and an overestimation of their own business "success" in making loans, and would of course be further supported by geopolitical ambitions.

This combination would inevitably lead to bad lending decisions, followed just as inevitably by debt restructuring, loan losses, and a contraction in development lending. In the 1920s, for example, the US set off quite explicitly and aggressively to displace England in...

Latin America, and American businesses and banks assumed they “understood” Latin America much better than the English did, in spite of the vast English experience there, but their early displacement of British lending only resulted in the huge loan losses of the 1930s.

The impression I get from Chinese friends involved in the lending process is that the real shock for Beijing occurred in 2014-15, when cratering oil prices left Venezuela in tatters, and China was forced reluctantly to provide first $4 billion in 2014 and then another $5...

billion in 2015 in cash-for-oil deals.

These and all its previous Venezuelan loans were then restructured for 3 years (and restructured again 3 years later). A friend of mine working on the deal told me at the time that all Latin American lending was now coming under...

much tighter scrutiny, and that there would be no new lending to Venezuela.

It is not surprising to me at all that this is when BRI lending peaked and began subsequently to fall. I don’t think Venezuela was the first loan...

More from Michael Pettis

More from Economy

On Jan 6, 2021, the always stellar Mr @deepakshenoy tweeted, this:

https://t.co/fa3GX9VnW0

Innocuous 1 sentence, but its a full economic theory at play.

Let me break it down for you. (1/n)

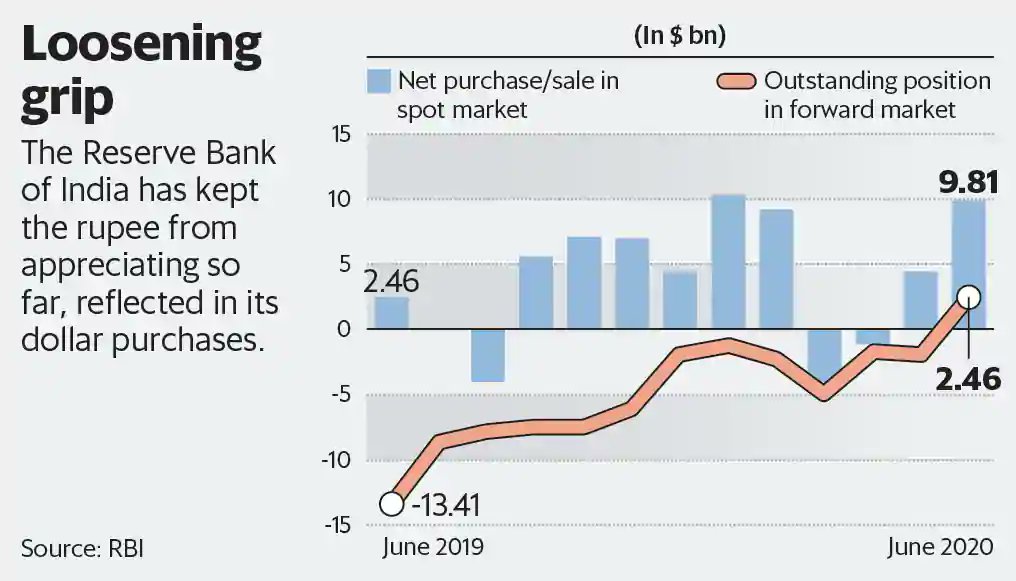

On September 30, 2020, I wrote an article for @CFASocietyIndia where I explained that RBI is all set to lose its ability to set interest rates if it continues to fiddle with the exchange rate (2/n)

What do I mean, "fiddle with the exchange rate"?

In essence, if RBI opts and continues to manage exchange rate, then that is "fiddling with the exchange rate"

RBI has done that in the past and has restarted it in 2020 - very explicitly. (3/n)

First in March 2020, it opened a Dollar/INR swap of $2B with far leg to be unwound in September 2020.

Implying INR will be bought from the open markets in order to prevent INR from falling vis a vis USD (4/n)

The Second aspect is now, that dollar inflow is happening, and the forex reserves swelled -> implying the rupee is appreciating, RBI again intervened from September, by selling INR in spot markets. (5/n)

https://t.co/9kpWP7ovyM

https://t.co/fa3GX9VnW0

Innocuous 1 sentence, but its a full economic theory at play.

Let me break it down for you. (1/n)

91 day TBills at 3.03%. Interest rates are even lower than RBI has them.

— Deepak Shenoy (@deepakshenoy) January 6, 2021

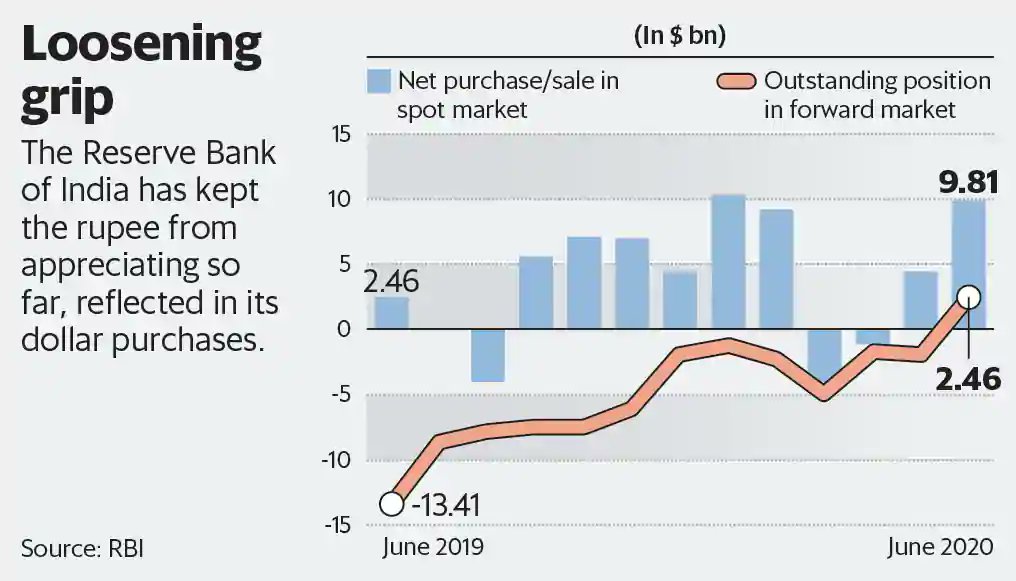

On September 30, 2020, I wrote an article for @CFASocietyIndia where I explained that RBI is all set to lose its ability to set interest rates if it continues to fiddle with the exchange rate (2/n)

What do I mean, "fiddle with the exchange rate"?

In essence, if RBI opts and continues to manage exchange rate, then that is "fiddling with the exchange rate"

RBI has done that in the past and has restarted it in 2020 - very explicitly. (3/n)

First in March 2020, it opened a Dollar/INR swap of $2B with far leg to be unwound in September 2020.

Implying INR will be bought from the open markets in order to prevent INR from falling vis a vis USD (4/n)

The Second aspect is now, that dollar inflow is happening, and the forex reserves swelled -> implying the rupee is appreciating, RBI again intervened from September, by selling INR in spot markets. (5/n)

https://t.co/9kpWP7ovyM

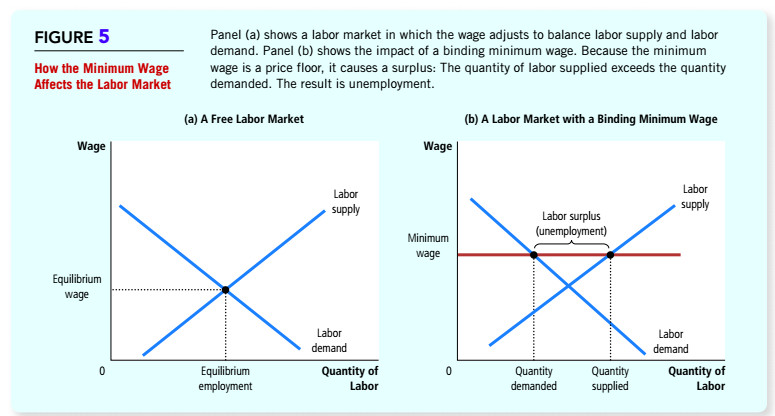

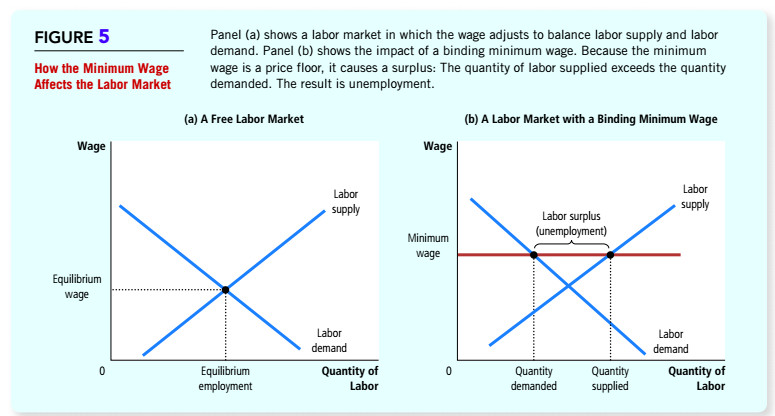

1/ To add a little texture to @NickHanauer's thread, it's important to recognize that there's a good reason why orthodox economists (& economic cosplayers) so vehemently oppose a $15 min wage:

The min wage is a wedge that threatens to undermine all of orthodox economic theory.

2/ Orthodox economics is grounded in two fundamental models: a systems model that describes the market as a closed equilibrium system, and a behavioral model that describes humans as rational, self-interested utility-maximizers. The modern min wage debate undermines both models.

3/ The assertion that a min wage kills jobs is so central to orthodox economics that it is often used as the textbook example of the Supply/Demand curve. Raise the cost of labor and businesses will buy less of it. It's literally Econ 101!

4/ Econ 101 insists that markets automatically set an efficient "equilibrium price" for labor & everything else. Mess with this price and bad things happen. Yet decades of empirical research has persuaded a majority of economists that this just isn't

5/ How can this be? Well, either the market is not a closed equilibrium system in which if you raise the price of labor employers automatically purchase less of it... OR the market is not automatically setting an efficient and fair equilibrium wage. Or maybe both. #FAIL

The min wage is a wedge that threatens to undermine all of orthodox economic theory.

1/4 Most people, especially academic economists, think that the controversy over the minimum wage is a contest over facts. It's not. It's a contest over power, status, and wealth. It is just like the contest over racial and gender justice.

— Nick Hanauer (@NickHanauer) January 17, 2021

2/ Orthodox economics is grounded in two fundamental models: a systems model that describes the market as a closed equilibrium system, and a behavioral model that describes humans as rational, self-interested utility-maximizers. The modern min wage debate undermines both models.

3/ The assertion that a min wage kills jobs is so central to orthodox economics that it is often used as the textbook example of the Supply/Demand curve. Raise the cost of labor and businesses will buy less of it. It's literally Econ 101!

4/ Econ 101 insists that markets automatically set an efficient "equilibrium price" for labor & everything else. Mess with this price and bad things happen. Yet decades of empirical research has persuaded a majority of economists that this just isn't

5/ How can this be? Well, either the market is not a closed equilibrium system in which if you raise the price of labor employers automatically purchase less of it... OR the market is not automatically setting an efficient and fair equilibrium wage. Or maybe both. #FAIL