The vast majority of images are jpegs, which are internally 420 YUV, but they get converted to 32 bit RGB for use in apps. Using native YUV formats would save half the memory and rendering bandwidth, speed loading, and provide a tiny quality improvement. It would also be \

More from Tech

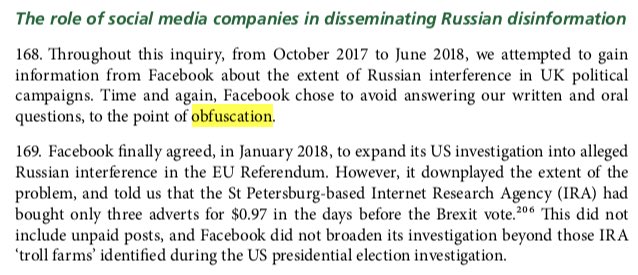

Ok, here. Just one of the 236 mentions of Facebook in the under read but incredibly important interim report from Parliament. ht @CommonsCMS https://t.co/gfhHCrOLeU

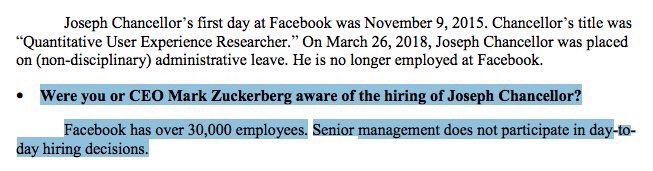

Let’s do another, this one to Senate Intel. Question: “Were you or CEO Mark Zuckerberg aware of the hiring of Joseph Chancellor?"

Answer "Facebook has over 30,000 employees. Senior management does not participate in day-today hiring decisions."

Or to @CommonsCMS: Question: "When did Mark Zuckerberg know about Cambridge Analytica?"

Answer: "He did not become aware of allegations CA may not have deleted data about FB users obtained through Dr. Kogan's app until March of 2018, when

these issues were raised in the media."

If you prefer visuals, watch this short clip after @IanCLucas rightly expresses concern about a Facebook exec failing to disclose info.

A company as powerful as @facebook should be subject to proper scrutiny. Mike Schroepfer, its CTO, told us that the buck stops with Mark Zuckerberg on the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which is why he should come and answer our questions @DamianCollins @IanCLucas pic.twitter.com/0H4VMhtIFu

— Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee (@CommonsCMS) May 23, 2018

You May Also Like

Pangolins, September 2019 and PLA are the key to this mystery

Stay Tuned!

1. Yang

Meet Yang Ruifu, CCP's biological weapons expert https://t.co/JjB9TLEO95 via @Gnews202064

— Billy Bostickson \U0001f3f4\U0001f441&\U0001f441 \U0001f193 (@BillyBostickson) October 11, 2020

Interesting expose of China's top bioweapons expert who oversaw fake pangolin research

Paper 1: https://t.co/TrXESKLYmJ

Paper 2:https://t.co/9LSJTNCn3l

Pangolinhttps://t.co/2FUAzWyOcv pic.twitter.com/I2QMXgnkBJ

2. A jacobin capuchin dangling a flagellin pangolin on a javelin while playing a mandolin and strangling a mannequin on a paladin's palanquin, said Saladin

More to come tomorrow!

3. Yigang Tong

https://t.co/CYtqYorhzH

Archived: https://t.co/ncz5ruwE2W

4. YT Interview

Some bats & pangolins carry viruses related with SARS-CoV-2, found in SE Asia and in Yunnan, & the pangolins carrying SARS-CoV-2 related viruses were smuggled from SE Asia, so there is a possibility that SARS-CoV-2 were coming from

To me, the most important aspect of the 2018 midterms wasn't even about partisan control, but about democracy and voting rights. That's the real battle.

2/The good news: It's now an issue that everyone's talking about, and that everyone cares about.

3/More good news: Florida's proposition to give felons voting rights won. But it didn't just win - it won with substantial support from Republican voters.

That suggests there is still SOME grassroots support for democracy that transcends

4/Yet more good news: Michigan made it easier to vote. Again, by plebiscite, showing broad support for voting rights as an

5/OK, now the bad news.

We seem to have accepted electoral dysfunction in Florida as a permanent thing. The 2000 election has never really

Bad ballot design led to a lot of undervotes for Bill Nelson in Broward Co., possibly even enough to cost him his Senate seat. They do appear to be real undervotes, though, instead of tabulation errors. He doesn't really seem to have a path to victory. https://t.co/utUhY2KTaR

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) November 16, 2018