Q: Didn't you say Bitcoin was going to keep rising to $100k?

A: That's one thing I actually wanted to talk about. We are pretty rigorous with our research. In fact, recently, we upgraded our research platform with an AI System...

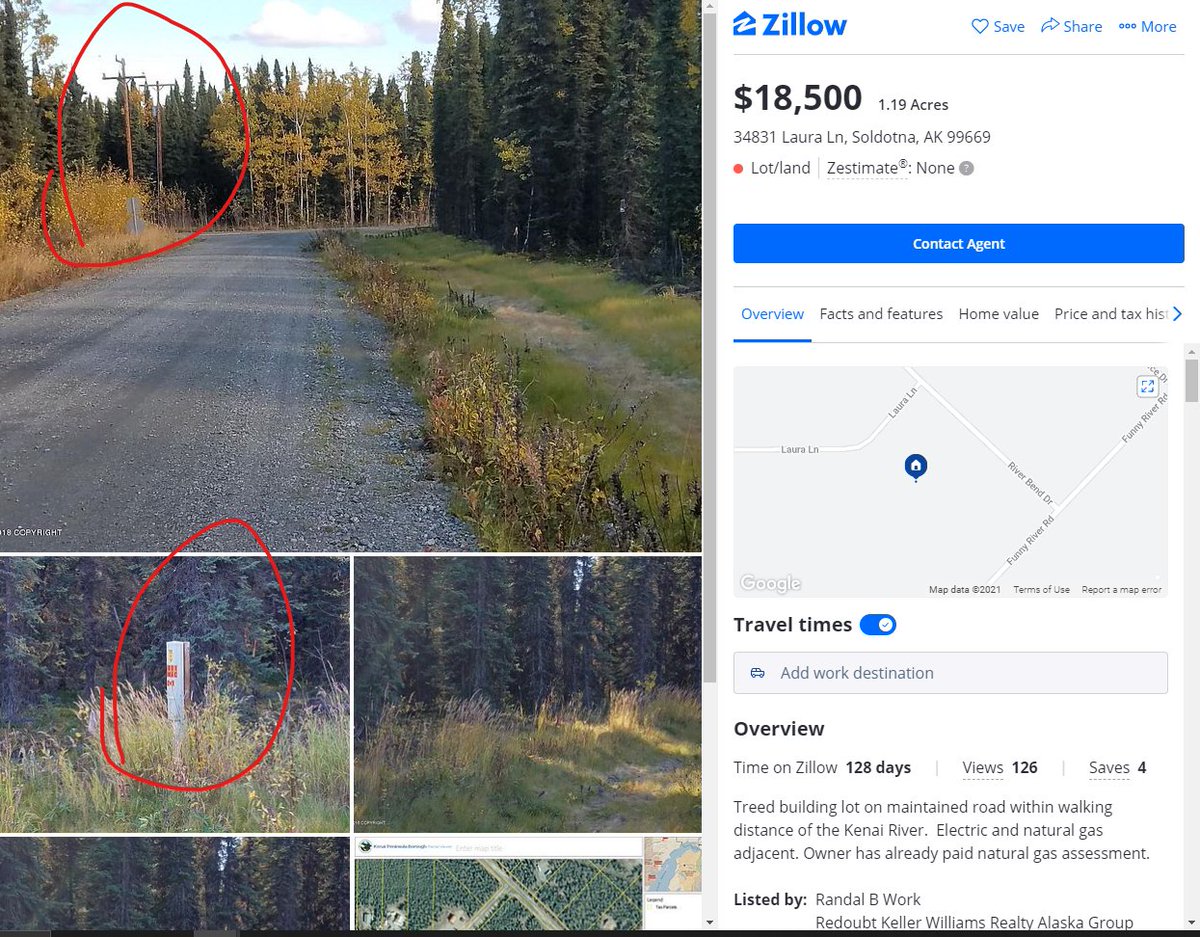

If I did thred on finding/acquiring decent raw land would that be something pepo are interested in

— Ovcharka (@ouroboros_outis) January 18, 2021

I think I know a bunch of weird tips/tricks for selection at this point that it might help u guys, lemme know

Ivor Cummins BE (Chem) is a former R&D Manager at HP (sourcre: https://t.co/Wbf5scf7gn), turned Content Creator/Podcast Host/YouTube personality. (Call it what you will.)

— Steve (@braidedmanga) November 17, 2020