A quick thread on intelligence analysis in the context of cyber threat intelligence. I see a number of CTI analysts get into near analysis paralysis phases for over thinking their assessments or over obsessing about if they might be wrong. (1/x)

More from Tech

There has been a lot of discussion about negative emissions technologies (NETs) lately. While we need to be skeptical of assumed planetary-scale engineering and wary of moral hazard, we also need much greater RD&D funding to keep our options open. A quick thread: 1/10

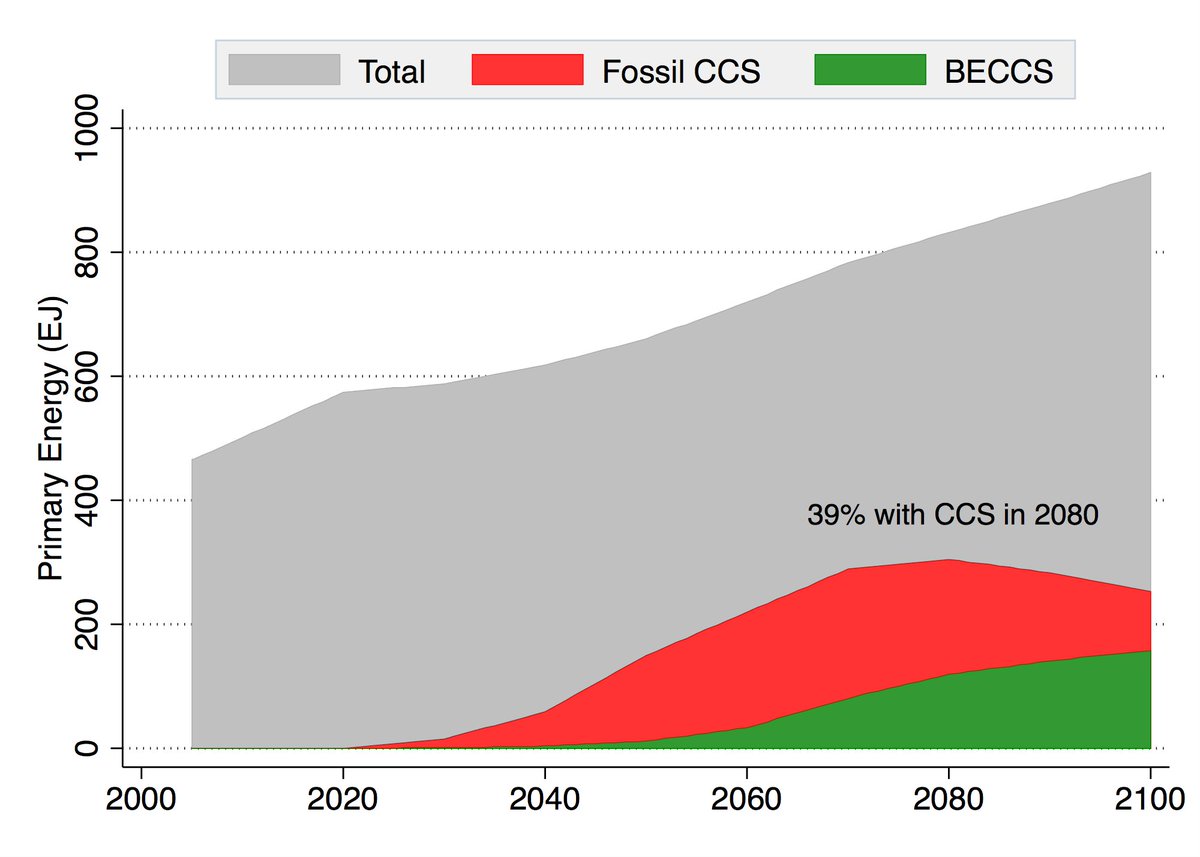

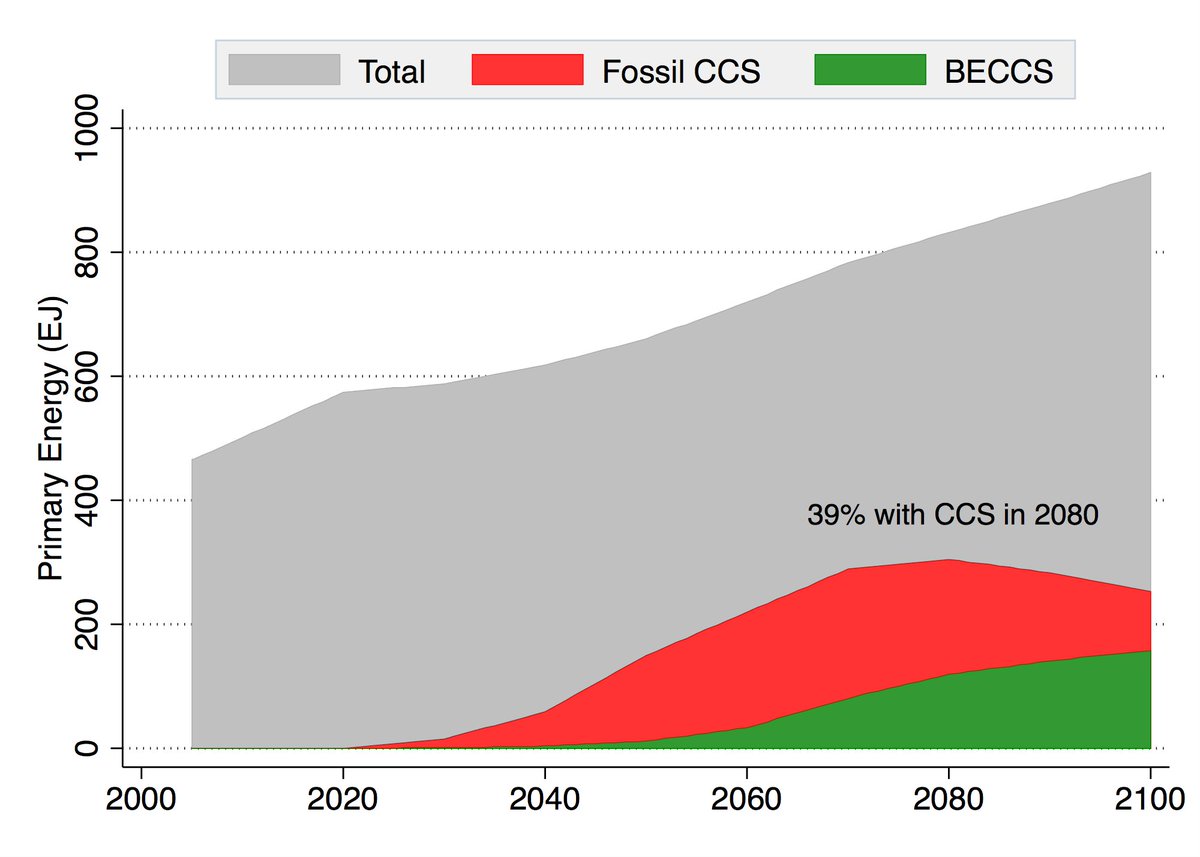

Energy system models love NETs, particularly for very rapid mitigation scenarios like 1.5C (where the alternative is zero global emissions by 2040)! More problematically, they also like tons of NETs in 2C scenarios where NETs are less essential. https://t.co/M3ACyD4cv7 2/10

In model world the math is simple: very rapid mitigation is expensive today, particularly once you get outside the power sector, and technological advancement may make later NETs cheaper than near-term mitigation after a point. 3/10

This is, of course, problematic if the aim is to ensure that particular targets (such as well-below 2C) are met; betting that a "backstop" technology that does not exist today at any meaningful scale will save the day is a hell of a moral hazard. 4/10

Many models go completely overboard with CCS, seeing a future resurgence of coal and a large part of global primary energy occurring with carbon capture. For example, here is what the MESSAGE SSP2-1.9 scenario shows: 5/10

Energy system models love NETs, particularly for very rapid mitigation scenarios like 1.5C (where the alternative is zero global emissions by 2040)! More problematically, they also like tons of NETs in 2C scenarios where NETs are less essential. https://t.co/M3ACyD4cv7 2/10

There is a lot of confusion about carbon budgets and how quickly emissions need to fall to zero to meet various warming targets. To cut through some of this morass, we can use some very simple emission pathways to explore what various targets would entail. 1/11 pic.twitter.com/Kriedtf0Ec

— Zeke Hausfather (@hausfath) September 24, 2020

In model world the math is simple: very rapid mitigation is expensive today, particularly once you get outside the power sector, and technological advancement may make later NETs cheaper than near-term mitigation after a point. 3/10

This is, of course, problematic if the aim is to ensure that particular targets (such as well-below 2C) are met; betting that a "backstop" technology that does not exist today at any meaningful scale will save the day is a hell of a moral hazard. 4/10

Many models go completely overboard with CCS, seeing a future resurgence of coal and a large part of global primary energy occurring with carbon capture. For example, here is what the MESSAGE SSP2-1.9 scenario shows: 5/10

You May Also Like

This is a pretty valiant attempt to defend the "Feminist Glaciology" article, which says conventional wisdom is wrong, and this is a solid piece of scholarship. I'll beg to differ, because I think Jeffery, here, is confusing scholarship with "saying things that seem right".

The article is, at heart, deeply weird, even essentialist. Here, for example, is the claim that proposing climate engineering is a "man" thing. Also a "man" thing: attempting to get distance from a topic, approaching it in a disinterested fashion.

Also a "man" thing—physical courage. (I guess, not quite: physical courage "co-constitutes" masculinist glaciology along with nationalism and colonialism.)

There's criticism of a New York Times article that talks about glaciology adventures, which makes a similar point.

At the heart of this chunk is the claim that glaciology excludes women because of a narrative of scientific objectivity and physical adventure. This is a strong claim! It's not enough to say, hey, sure, sounds good. Is it true?

Imagine for a moment the most obscurantist, jargon-filled, po-mo article the politically correct academy might produce. Pure SJW nonsense. Got it? Chances are you're imagining something like the infamous "Feminist Glaciology" article from a few years back.https://t.co/NRaWNREBvR pic.twitter.com/qtSFBYY80S

— Jeffrey Sachs (@JeffreyASachs) October 13, 2018

The article is, at heart, deeply weird, even essentialist. Here, for example, is the claim that proposing climate engineering is a "man" thing. Also a "man" thing: attempting to get distance from a topic, approaching it in a disinterested fashion.

Also a "man" thing—physical courage. (I guess, not quite: physical courage "co-constitutes" masculinist glaciology along with nationalism and colonialism.)

There's criticism of a New York Times article that talks about glaciology adventures, which makes a similar point.

At the heart of this chunk is the claim that glaciology excludes women because of a narrative of scientific objectivity and physical adventure. This is a strong claim! It's not enough to say, hey, sure, sounds good. Is it true?