Hot take: Courts might be able to review the legality of this impeachment, even under current political-question doctrine. Here’s why and how the issue might arise:

Honest Q: Some people argue in good faith that an impeachment trial after POTUS leaves office is unconstitutional. I think they\u2019re wrong. But let\u2019s say they\u2019re right, yet senate does it anyway. Does anyone seriously think SCOTUS reverses verdict (or even can)?

— Jonah Goldberg (@JonahDispatch) January 17, 2021

More from Law

High crime talk from Fredo

VA curfew

Sen. Grassley - Biden family investigated, potential financial crimes WW including China

Warning

March

The #TexasCase has them terrified.

— Major Patriot (@MajorPatriot) December 10, 2020

They are losing it.#CNN pic.twitter.com/FtdWKIXBlB

VA curfew

#BREAKING: Virginia will implement a statewide curfew from midnight to 5 a.m. starting on Dec. 14. Here's what else is changing for Virginians.https://t.co/cH4jdCOZgt

— WUSA9 (@wusa9) December 10, 2020

Sen. Grassley - Biden family investigated, potential financial crimes WW including China

Warning

— Dan Scavino\U0001f1fa\U0001f1f8\U0001f985 (@DanScavino) December 11, 2020

March

Some WESC submissions that are worth a read....(my thread of bookmarks)

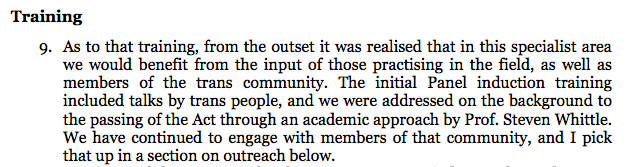

Judge Paula Grey is president of the Gender Recognition Panel

She doesn't make any recommendations, but she sets out how the process currently works

Which chimes with my analysis of the GRP User Panel and statistics https://t.co/XixEz7lNJv

She is also co-author if the Equal Treatment Bench Book and writes about how the judges are trained by Gendered Intelligence

There is the government's own response

https://t.co/bOn9XecAkz

On single sex spaces they say the law is clear that service providers are able to restrict access to spaces on the basis of biological sex where there is clear justification.

The response from @womensaid is significant.

Their members want trans survivors to get support they need but not by undermining their ability to serve women with female staff & female only services

They highlight lack of clarity

https://t.co/p7096sZcos

This was their position in 2015

They have moved on alot - they have been consulting with members since last year, and have had the courage to say what their members told them, not what Stonewall wanted to

Judge Paula Grey is president of the Gender Recognition Panel

She doesn't make any recommendations, but she sets out how the process currently works

Which chimes with my analysis of the GRP User Panel and statistics https://t.co/XixEz7lNJv

She is also co-author if the Equal Treatment Bench Book and writes about how the judges are trained by Gendered Intelligence

There is the government's own response

https://t.co/bOn9XecAkz

On single sex spaces they say the law is clear that service providers are able to restrict access to spaces on the basis of biological sex where there is clear justification.

The response from @womensaid is significant.

Their members want trans survivors to get support they need but not by undermining their ability to serve women with female staff & female only services

They highlight lack of clarity

https://t.co/p7096sZcos

This was their position in 2015

They have moved on alot - they have been consulting with members since last year, and have had the courage to say what their members told them, not what Stonewall wanted to