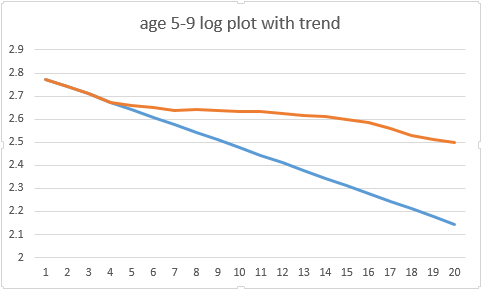

I've had a lot of positive comments on this theory, and some helpful challenges. The most common of which was: surely a single-day effect wouldn't be big enough to cause the 'twist' in the data that we're seeing in those age groups? So I set out to find out if it was (thread)

So I have a theory on this. And if I'm right, there's bad news about that acceleration in the overall case trend, and possibly good news about vaccines in the over-80s. WARNING: This is going to be another long, maths-y thread (involving cubic coefficients this time!) https://t.co/EiszSAIL9t

— James Ward (@JamesWard73) January 29, 2021

More from For later read

@KevinCoates correct me if I'm wrong, but basic point seems to be that banning targeted ads will lower platform profits, but will mostly be beneficial for consumers.

Some counterpoints 👇

That targeted ads allow for "free" products for consumers is a common talking point and we're going to see more of it in the coming months.: https://t.co/Xty3My3f0u (1/14)

— Kevin Coates (@KevinCoates) February 16, 2021

1) This assumes that consumers prefer contextual ads to targeted ones.

This does not seem self-evident to me

Great post by @Sherman1890 got me thinking about the future of targeted ads.

— Dirk Auer (@AuerDirk) February 12, 2021

More and more tools (privacy labels, ad blockers, GDPR) enable consumers to opt-out from targeted ads - can limit the data platforms receive or block ads altogether.

The end of targeted ads? \U0001f9f5\U0001f447 https://t.co/MA6A3BrUWq

Research also finds that firms choose between ad. targeting vs. obtrusiveness 👇

If true, the right question is not whether consumers prefer contextual ads to targeted ones. But whether they prefer *more* contextual ads vs *fewer* targeted

2) True, many inframarginal platforms might simply shift to contextual ads.

But some might already be almost indifferent between direct & indirect monetization.

Hard to imagine that *none* of them will respond to reduced ad revenue with actual fees.

3) Policy debate seems to be moving from:

"Consumers are insufficiently informed to decide how they share their data."

To

"No one in their right mind would agree to highly targeted ads (e.g., those that mix data from multiple sources)."

IMO the latter statement is incorrect.

You May Also Like

Always. No, your company is not an exception.

A tactic I don’t appreciate at all because of how unfairly it penalizes low-leverage, junior employees, and those loyal enough not to question it, but that’s negotiation for you after all. Weaponized information asymmetry.

Listen to Aditya

"we don't negotiate salaries" really means "we'd prefer to negotiate massive signing bonuses and equity grants, but we'll negotiate salary if you REALLY insist" https://t.co/80k7nWAMoK

— Aditya Mukerjee, the Otterrific \U0001f3f3\ufe0f\u200d\U0001f308 (@chimeracoder) December 4, 2018

And by the way, you should never be worried that an offer would be withdrawn if you politely negotiate.

I have seen this happen *extremely* rarely, mostly to women, and anyway is a giant red flag. It suggests you probably didn’t want to work there.

You wish there was no negotiating so it would all be more fair? I feel you, but it’s not happening.

Instead, negotiate hard, use your privilege, and then go and share numbers with your underrepresented and underpaid colleagues. […]

If everyone was holding bitcoin on the old x86 in their parents basement, we would be finding a price bottom. The problem is the risk is all pooled at a few brokerages and a network of rotten exchanges with counter party risk that makes AIG circa 2008 look like a good credit.

— Greg Wester (@gwestr) November 25, 2018

The benign product is sovereign programmable money, which is historically a niche interest of folks with a relatively clustered set of beliefs about the state, the literary merit of Snow Crash, and the utility of gold to the modern economy.

This product has narrow appeal and, accordingly, is worth about as much as everything else on a 486 sitting in someone's basement is worth.

The other product is investment scams, which have approximately the best product market fit of anything produced by humans. In no age, in no country, in no city, at no level of sophistication do people consistently say "Actually I would prefer not to get money for nothing."

This product needs the exchanges like they need oxygen, because the value of it is directly tied to having payment rails to move real currency into the ecosystem and some jurisdictional and regulatory legerdemain to stay one step ahead of the banhammer.