The Northman and Honour Cultures - a brief thread

One of the most distinctive marks of Robert Eggers' latest film The Northman, much like his prior work, is the refusal to condescend to, censor, or otherwise alter the views of past people. This is also its greatest weakness.

More from All

You May Also Like

Joshua Hawley, Missouri's Junior Senator, is an autocrat in waiting.

His arrogance and ambition prohibit any allegiance to morality or character.

Thus far, his plan to seize the presidency has fallen into place.

An explanation in photographs.

🧵

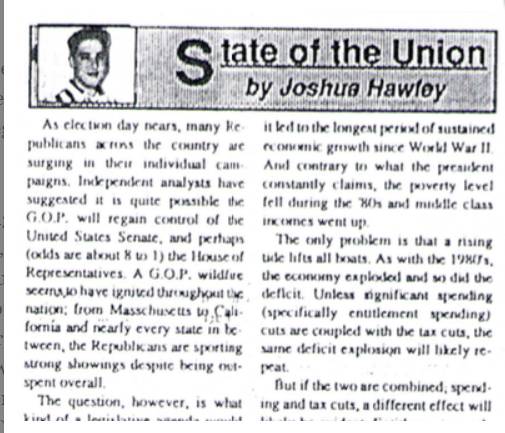

Joshua grew up in the next town over from mine, in Lexington, Missouri. A a teenager he wrote a column for the local paper, where he perfected his political condescension.

2/

By the time he reached high-school, however, he attended an elite private high-school 60 miles away in Kansas City.

This is a piece of his history he works to erase as he builds up his counterfeit image as a rural farm boy from a small town who grew up farming.

3/

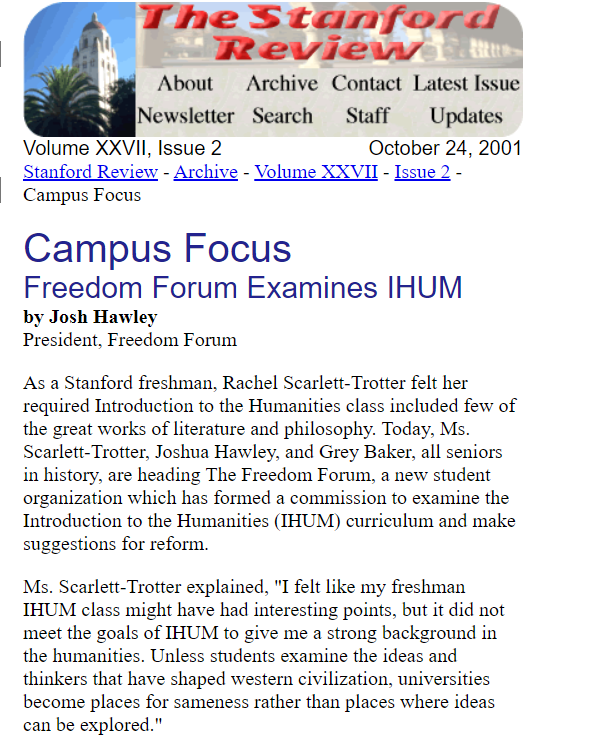

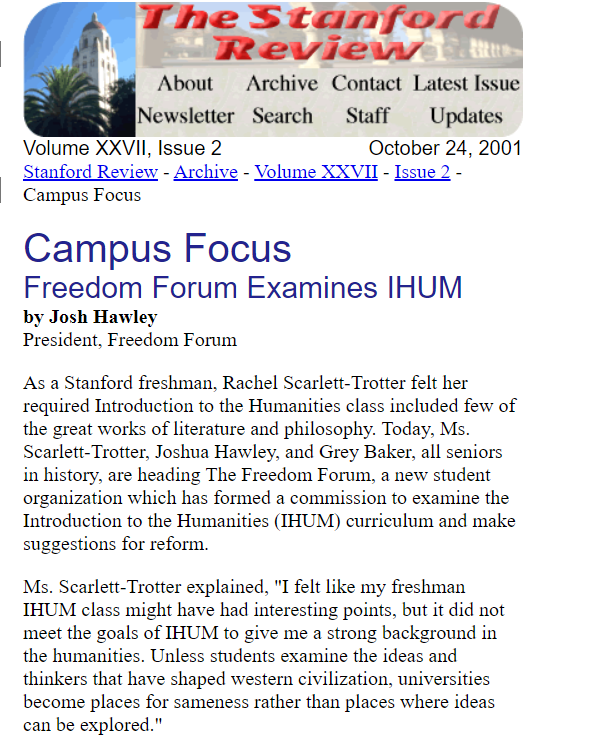

After graduating from Rockhurst High School, he attended Stanford University where he wrote for the Stanford Review--a libertarian publication founded by Peter Thiel..

4/

(Full Link: https://t.co/zixs1HazLk)

Hawley's writing during his early 20s reveals that he wished for the curriculum at Stanford and other "liberal institutions" to change and to incorporate more conservative moral values.

This led him to create the "Freedom Forum."

5/

His arrogance and ambition prohibit any allegiance to morality or character.

Thus far, his plan to seize the presidency has fallen into place.

An explanation in photographs.

🧵

Joshua grew up in the next town over from mine, in Lexington, Missouri. A a teenager he wrote a column for the local paper, where he perfected his political condescension.

2/

By the time he reached high-school, however, he attended an elite private high-school 60 miles away in Kansas City.

This is a piece of his history he works to erase as he builds up his counterfeit image as a rural farm boy from a small town who grew up farming.

3/

After graduating from Rockhurst High School, he attended Stanford University where he wrote for the Stanford Review--a libertarian publication founded by Peter Thiel..

4/

(Full Link: https://t.co/zixs1HazLk)

Hawley's writing during his early 20s reveals that he wished for the curriculum at Stanford and other "liberal institutions" to change and to incorporate more conservative moral values.

This led him to create the "Freedom Forum."

5/

These 10 threads will teach you more than reading 100 books

Five billionaires share their top lessons on startups, life and entrepreneurship (1/10)

10 competitive advantages that will trump talent (2/10)

Some harsh truths you probably don’t want to hear (3/10)

10 significant lies you’re told about the world (4/10)

Five billionaires share their top lessons on startups, life and entrepreneurship (1/10)

I interviewed 5 billionaires this week

— GREG ISENBERG (@gregisenberg) January 23, 2021

I asked them to share their lessons learned on startups, life and entrepreneurship:

Here's what they told me:

10 competitive advantages that will trump talent (2/10)

To outperform, you need serious competitive advantages.

— Sahil Bloom (@SahilBloom) March 20, 2021

But contrary to what you have been told, most of them don't require talent.

10 competitive advantages that you can start developing today:

Some harsh truths you probably don’t want to hear (3/10)

I\u2019ve gotten a lot of bad advice in my career and I see even more of it here on Twitter.

— Nick Huber (@sweatystartup) January 3, 2021

Time for a stiff drink and some truth you probably dont want to hear.

\U0001f447\U0001f447

10 significant lies you’re told about the world (4/10)

THREAD: 10 significant lies you're told about the world.

— Julian Shapiro (@Julian) January 9, 2021

On startups, writing, and your career:

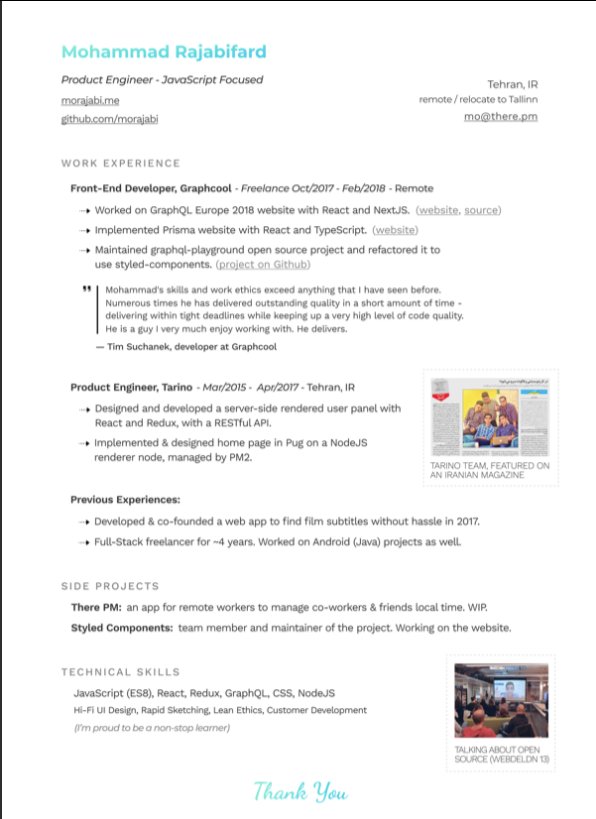

👨💻 Last resume I sent to a startup one year ago, sharing with you to get ideas:

- Forget what you don't have, make your strength bold

- Pick one work experience and explain what you did in detail w/ bullet points

- Write it towards the role you apply

- Give social proof

/thread

"But I got no work experience..."

Make a open source lib, make a small side project for yourself, do freelance work, ask friends to work with them, no friends? Find friends on Github, and Twitter.

Bonus points:

- Show you care about the company: I used the company's brand font and gradient for in the resume for my name and "Thank You" note.

- Don't list 15 things and libraries you worked with, pick the most related ones to the role you're applying.

-🙅♂️"copy cover letter"

"I got no firends, no work"

One practical way is to reach out to conferences and offer to make their website for free. But make sure to do it good. You'll get:

- a project for portfolio

- new friends

- work experience

- learnt new stuff

- new thing for Twitter bio

If you don't even have the skills yet, why not try your chance for @LambdaSchool? No? @freeCodeCamp. Still not? Pick something from here and learn https://t.co/7NPS1zbLTi

You'll feel very overwhelmed, no escape, just acknowledge it and keep pushing.

- Forget what you don't have, make your strength bold

- Pick one work experience and explain what you did in detail w/ bullet points

- Write it towards the role you apply

- Give social proof

/thread

"But I got no work experience..."

Make a open source lib, make a small side project for yourself, do freelance work, ask friends to work with them, no friends? Find friends on Github, and Twitter.

Bonus points:

- Show you care about the company: I used the company's brand font and gradient for in the resume for my name and "Thank You" note.

- Don't list 15 things and libraries you worked with, pick the most related ones to the role you're applying.

-🙅♂️"copy cover letter"

"I got no firends, no work"

One practical way is to reach out to conferences and offer to make their website for free. But make sure to do it good. You'll get:

- a project for portfolio

- new friends

- work experience

- learnt new stuff

- new thing for Twitter bio

If you don't even have the skills yet, why not try your chance for @LambdaSchool? No? @freeCodeCamp. Still not? Pick something from here and learn https://t.co/7NPS1zbLTi

You'll feel very overwhelmed, no escape, just acknowledge it and keep pushing.